A quick site update

Link to heading

First real post of the year! I’ve made some updates to the site, so this post will be somewhat content-light. I have decided that if I’m going to actually use this blog, I have to sit down and force myself to write something, and that means I need a schedule. For now I’ve committed to biweekly posts. Should be a quick enough pace to keep me engaged but still enable research and proofreading for more involved writing.

I’m not placing a limit on what I write about - It may be software, entertainment, politics, or just something I had on my mind that day. The goal is to encourage myself to write regardless of the contents, but I’m aiming to have some actual quality on here by the end of the year. If all goes well, that will mean 26 posts by Christmas!

If you don’t care about software dev, don’t worry; I have a bunch of posts lined up, covering topics like liminal spaces and urbanism, Final Fantasy, honesty in political discourse, and the ethics of bad media. There’ll be meat on these bones soon.

The problem Link to heading

I work in software, and one of the things I like most about my job is finding ways to work more effectively. I am by no means the kind of person to “get on that grind” or “hustle” - I value my own wellbeing too much for that. I simply appreciate a well-oiled machine, and like facilitating more effective work where I can. Two areas of improvement I often notice in my work and open-source projects are repository maintenance and task management. I thought it might be valuable to share some relevant insights I’ve taken away from my work.

In general, there are three principles I try to follow when making contributions to a codebase, whether at work or on open-source projects:

1. Be informative Link to heading

Name branches clearly. Link to heading

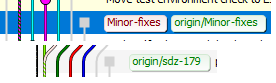

At my job, we often run into situations where we want to reference code changes being made, but the git branch in question is named something arcane like “fixes” or “Issue-132”. Any time we want to discuss the change, we need to look at the issue tracker and search for the item. It’s hardly the worst thing, but it is needlessly laborious and it slows our meetings down to a crawl.

This may seem obvious, but when creating a new branch, a good name is critical. A good branch name makes identifying its purpose and even its contents much easier. A team should be able to tell at a glance what issue your branch is meant to address. If you’re using project management software like Jira or Trello, refer to ticket numbers in some way. Ideally, you shouldn’t have to root around in Jira during meetings just to understand who’s working on what.

Write clear commit messages. Link to heading

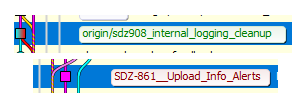

A clear and concise commit message helps developers keep track of what work has been performed in a branch, and when that work was done. A commit that reads “Removed unused getUserInfo() method” lets a reader easily pinpoint that specific change during review. A good comment also offers context for a change. Some code changes have a non-obvious effect, meaning a good comment can give a reader insight into why a change was made.

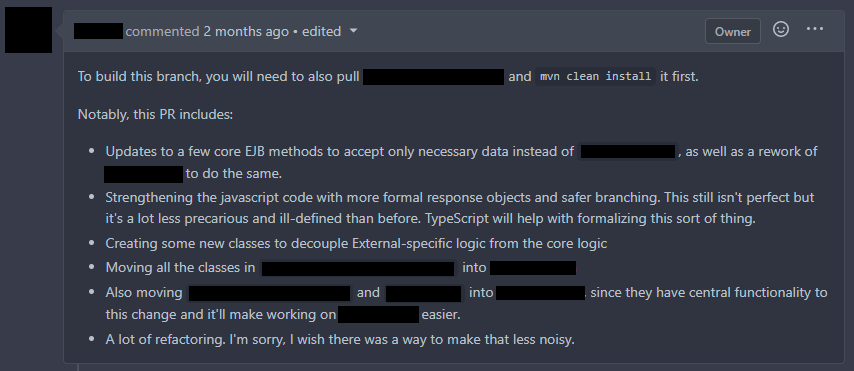

This PR clearly lists all the information you need to know at a glance.

Comments like “Review changes” or “fixes” require a reader to examine the change just to understand what was done, which takes time and mental resources away from the review process itself. The whole point of storing messages with each commit is to reduce the mental load on developers, so make use of them in your team!

2. Keep changes small Link to heading

Make smaller commits more often Link to heading

“Small” is relative to the task being performed, of course. You may need to update 15 files just to make one change (e.g. merging repeated code into one location) but all that work is in service of a single change. That one change should be your entire commit. Alternatively, you might be performing a few changes: Fixing a spelling mistake, removing unused code, and cleaning up comments. For small fixes like this, grouping them together is fine. Just make sure to document what you’ve done.

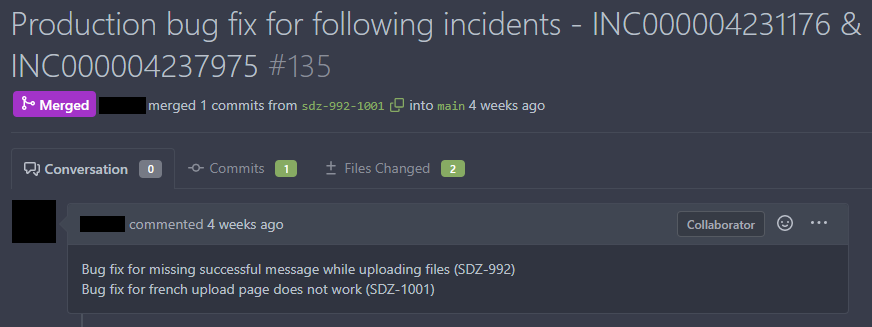

Early on in my current work project, there were a number of instances where a dev opened a pull request with 40 altered files across 3 commits. There’s simply not enough space to communicate what was changed in any one of those commits, even if the dev had bothered to write comments for them. Reviewing those PRs was a nightmare, and it could have been avoided.

I’m guilty of getting into the zone with my work and forgetting to commit changes, but it’s something I try to be mindful of. If you’re attentive to your progress and break up your work into atomic tasks, you can avoid this scenario and make your changes much easier to follow.

Actually, it was worse than that. It was 63 files spread across three tickets.

Avoid scope creep Link to heading

New tasks, fixes, and nice-to-haves have a nasty habit of working their way into your pull requests and mutating them into a huge, unmanageable mess. Avoiding scope creep is really a matter of good task analysis, but it has implications for your codebase as well.

For example: if during development you realize your current task cannot be completed without a separate, significant change, consider creating a new task in your issue tracker and creating a corresponding branch in git for the new work. Every situation is different; You may need to place your current branch on hold so that new work can be done to support it. You may be able to complete the work in your branch before moving on to the next one, or work might continue in parallel.

It’s tempting to identify bugs and fixes you can lump into current work, but doing so risks growing your branch into a multi-headed hydra containing multiple interlocking pieces, which blocks or is blocked by other work. It slows down the whole team and makes PR review a headache.

How to split up work is a subjective call you have to make yourself, but it shines a light on the importance of good up-front task analysis, and performing regular analysis on ongoing work. Is the work in this branch still in-scope for the task it’s assigned? Does new work need to be done, and should it receive its own branch? Will making a change block other work? These are the sorts of questions we should ask ourselves as devs regularly throughout the development process.

3. Cooperative Code Review Link to heading

Finally: when creating a pull request, both the primary dev and reviewers can do a few things to make each others’ lives easier.

Write a summary for your pull request Link to heading

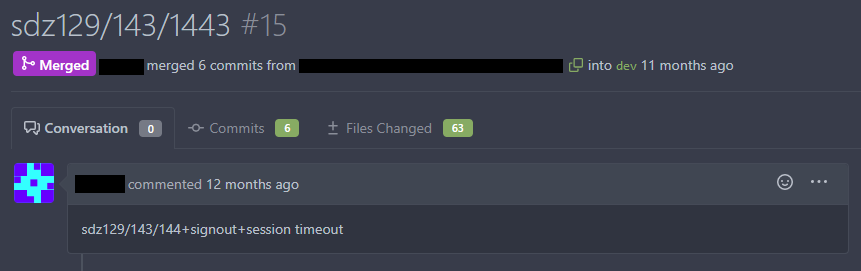

Not every PR requires a summary, but large ones with many changes should offer a reviewer a glimpse of major changes. Significant chunks of code may have been entirely overhauled and it may not be apparent to a reviewer how all the pieces fit together. A reviewing dev should be building and examining your code anyways, but offering insight into what changes were made and why can help resolve confusion for someone who hasn’t been living with your code for a week.

Not every pull request needs this level of detail, but this was a big change.

Write helpful comments Link to heading

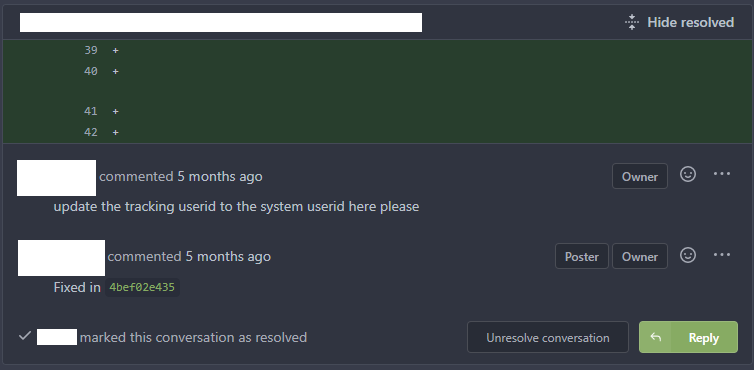

As the branch developer, respond to reviews with comments that indicate a resolution to the problem. When you’re done fixing a bug, offer a notice that the work was done and include the commit hash so the reviewer can easily see how their issue was addressed. If you decide a fix will not be made, provide justification (e.g. “Out of scope” or “To be addressed later”).

Resolve change requests Link to heading

Be timely when resolving comments! Though, it’s worth discussing with your team who should be responsible for resolving comments as fixes are made. In my team, I typically like to resolve comments myself as I make changes. If a comment needs to be re-opened, it can be. However, some may prefer for the commenter to resolve issues after they’ve had the chance to look over the requested changes. Ultimately it’s up to you, but either way it can help to keep everyone in sync.

I find that marking the commit of each change makes it easier to perform code review.

Review code thoroughly Link to heading

When reviewing a pull request, read the code and test the changes yourself. Reviewing without testing is counterproductive and leads to bugs. Too often (and I am guilty of this as well) I find that some pull requests will get a once-over and an approval with no comments. Some PRs are going to be simple enough changes, like config or locale string updates. But if your code is changing, it serves everyone on your team to give the changes a test. (And as discussed previously, a pull request with a description makes this process easier on the reviewer testing the code!)

But most importantly… Link to heading

Ask questions. If you aren’t sure what a piece of code is for, if you aren’t sure what your team’s procedures are, if you don’t remember the point of a specific change, don’t be afraid to ask for help! There’s always room for learning.